As we approach the holiday called Thanksgiving, how can we move past the American myths that support colonization, and find ways to decolonize our minds and our communities? I have not been able to blog recently, but want to share with you elements of a worship service on this topic I led on November 19th.

Opening Words

Opening Words

It is always good to give thanks! All that we have is a gift from life. Our food, our relationships, our shelter from the cold. And when we give thanks, it is always good to be mindful of all people, and notice those who are suffering and do what we can to ease suffering and change its causes. Today we give thanks, and we explore suffering. We must always do both together, so that our hearts are strong for the journey.

Before our Centering Music:

When you came into church today, the ushers handed each of you four slips of paper. I invite you to write on those four slips of paper the names of things that are precious to you—perhaps people, perhaps values, perhaps places—it could be anything. Perhaps what you are most thankful for. I invite you to keep those four slips in a pocket or purse, or hold them in your hand. We’ll come back to them later in the service.

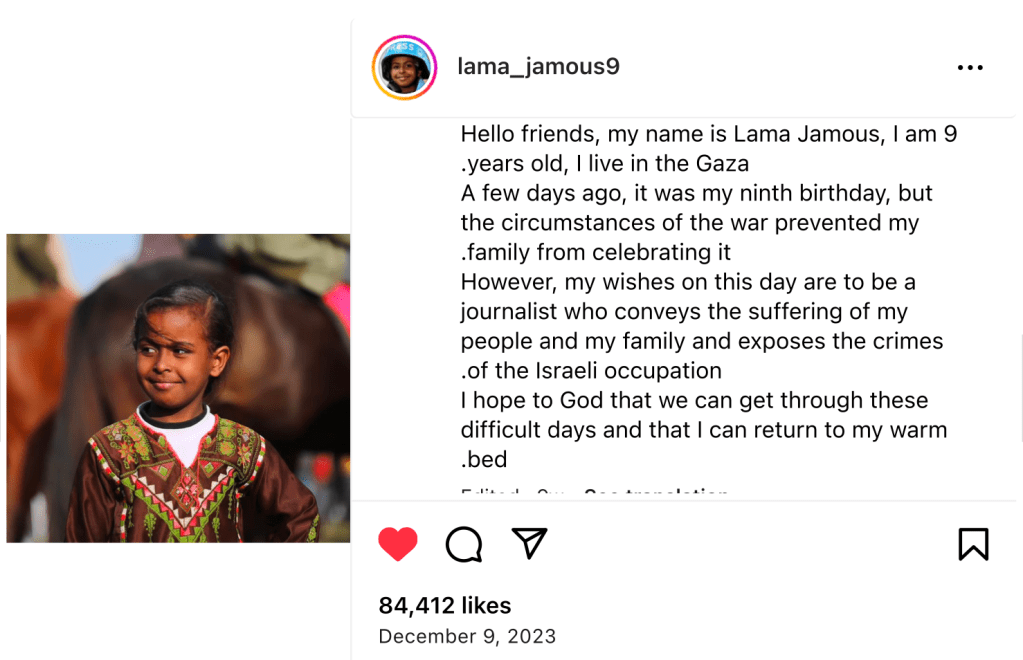

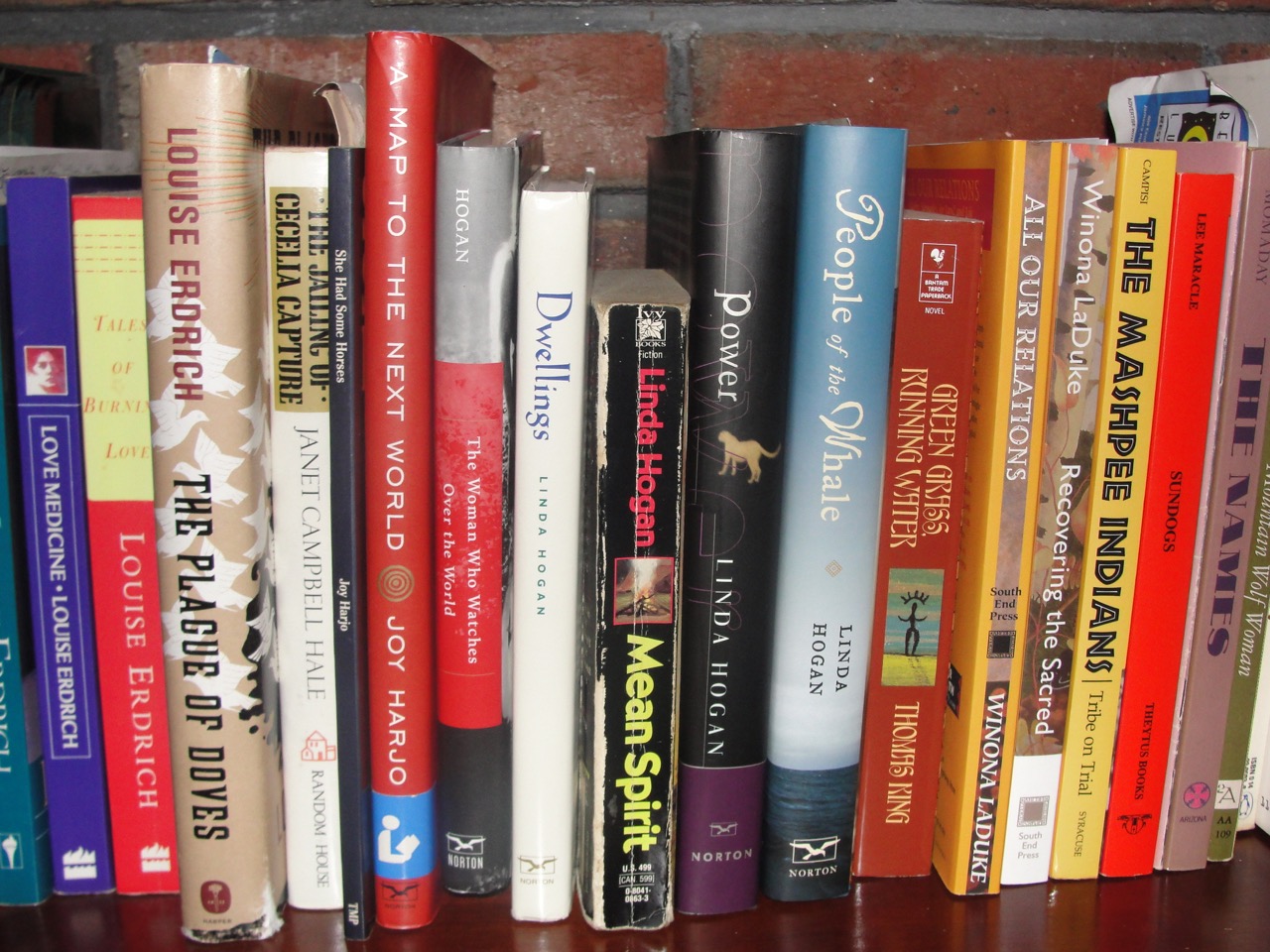

Reading: “I am tired of being invisible to you all” Winona LaDuke

Winona LaDuke is the executive director of Honor the Earth, and an Ojibwe activist and economist on Minnesota’s White Earth Reservation. She writes:

Winona LaDuke is the executive director of Honor the Earth, and an Ojibwe activist and economist on Minnesota’s White Earth Reservation. She writes:

There is this magical made-up time between Columbus Day (or Indigenous People’s Day for the enlightened) and Thanksgiving where white Americans think about native people. That’s sort of our window. November is Native American Heritage month. Before that, of course, is Halloween. Until about three years ago, one of the most popular Halloween costumes was Pocahontas. People know nothing about us, but they like to dress up like us or have us as a mascot.

We are invisible. Take it from me. I travel a lot, and often ask this question: Can you name 10 indigenous nations? Often, no one can name us. The most common nations named are Lakota, Cherokee, Navajo, Cheyenne and Blackfeet—mostly native people from western movies. This is the problem with history. If you make the victim disappear, there is no crime. And we just disappeared.

…But here’s what I want people to know today about native Americans: There are over 700 indigenous nations in North America. …We are doctors, lawyers, writers, educators, and we are here. We are land-based, and intend to stay that way. … America was stolen or purchased for a pittance. …Of the 4 percent of our land base which remains, we intend to keep it. …

I am tired of being invisible to you all. …What I want to say is that we are beautiful, amazing, tough-as-can-be people. It would be nice if we thought of each other kindly and with compassion. I am certainly not too tired to battle, but I would really like us all to do our part, beyond Native American Heritage Month.

Reflection on Living into History

Winona LaDuke asks, “Can you name ten Indigenous nations?” I am going to simplify her question—how many of us can name the four Indigenous nations whose territories lie in what we call the state of Maine? I am not going to put anyone on the spot—I invite you just to think about it in your own mind. If you can name those nations, think about how you learned about them and why. If you cannot name those nations, think about why that might be something no one ever taught you.

Remember what LaDuke said, “If you make the victim disappear, there is no crime.” In 1875, citizens of Maine passed an amendment to the state constitution that would forbid, in all future printings of the constitution, the printing of several sections of Article Ten. Some of these sections were obsolete instructions about the forming of the state of Maine. But one section was about the new State’s obligations to Indians within the territory. These hidden sections of the constitution would remain in force, but could no longer be read.

The four nations, by the way, are Penobscot, Passamaquoddy, Micmac, and Maliseet, and collectively they are part of the Wabanaki confederacy. [There were many other nations who lived here, but these are the contemporary recognized nations.] Two years ago, the Maliseet Representative to the State Legislature, Henry Bear, petitioned for a bill to make those sections available, and now, though they are still not printed with the constitution, they can be found on the website of the legislature. Here is part of the critical passage:

The new State [that is, Maine] shall, as soon as the necessary arrangements can be made for that purpose, assume and perform all the duties and obligations of this Commonwealth [that is Massachusetts], towards the Indians within said District of Maine, whether the same arise from treaties, or otherwise; and for this purpose shall obtain the assent of said Indians, and their release to this Commonwealth of claims and stipulations arising under the treaty at present existing between the said Commonwealth and said Indians;4

A 2015 article in the Portland Press Herald by Colin Woodard points out that it also

“directs Maine to set aside land valued at $30,000 for tribal use, at a time when undeveloped land in Maine sold for between 3 and 4 cents an acre. In 1967, Maine’s first Indian affairs commissioner, anthropologist Edward Hinckley, discovered Maine had received $30,000 from Massachusetts in compensation, but the state never actually set aside new land for the tribes.”

“If you make the victim disappear, there is no crime.”

And so, every autumn between October 12th and the fourth Thursday in November, we find ourselves once again in the season of false and misleading stories about European settlers and Native Americans. The story that Columbus discovered America in 1492. The story about the feast of the Pilgrims and the Indians described as the first Thanksgiving.

What influence does the past hold over the present? History shapes the social landscape of today, but our social landscape also shapes the stories we canonize as history. A mythology about benign ancestors settling a new land is part of what ensures the continuity of the ongoing process of colonization. How can we reckon with the past, to live in greater wholeness in the present?

I realize, each Sunday, as we gather in worship, that many, if not most of us, are going around these days in some state of trauma. We are watching democracy fall under the weight of plutocracy, we are witnessing climate change’s effects in mega-storms and forest fires, we are watching the rise of neo-Nazi’s and attacks on immigrants. Many of us are fighting against the attempt to take away health care from millions, and a tax plan being voted on in Congress that might better be described as a huge theft from the majority of American citizens to benefit the richest 1 percent. The list could go on and on. Even to read the news these days can be a trigger for trauma.

So I ask myself when I prepare for worship, how do we come together in the midst of trauma? How can I ease the burdens that people are carrying, rather than add to them? And is there any value in sharing difficult information? I come back to that indelible link between history and the present day. If we don’t understand our history, we won’t be able to understand the present day. If we believe the myths that are told to us about our history, we won’t be able to pierce through to the truth within the myths that are generated today to keep us in confusion.

For the past year and a half, I have been involved in a Maine-Wabanaki REACH sponsored project called “Decolonizing Faith.” Led by a group of Wabanaki and non-Wabanaki people in partnership, we operate on the belief that decolonizing our minds and our communities means learning about and acknowledging the full truth of the past and the full truth of the present. It means committing to creating a just future, despite the obstacles.

The process of decolonizing ourselves as non-Indigenous people begins with letting go of guilt and instead opening to feelings of grief and anger in response to centuries of genocide and white domination. It means recognizing and acknowledging the benefits that have come to us because of colonization, and holding ourselves accountable for what is happening now. It means turning away from the complacency encouraged by mainstream culture, toward resisting further harm.

Maria Girouard, a member of the Penobscot Nation, spoke at a 2014 gathering sponsored by Maine Wabanaki REACH, about the possibility for hope in these times. She said,

Everything that Native peoples have had to endure has been prophesized by my ancestors. A series of prophesies now referred to as the Seven Fires Prophesies describe all these eras or epochs through which Native peoples were going to have to live. Each era or epoch was called a fire. The seventh fire in the Seven Fires Prophesies talks about a time when the world is befouled, when the rivers and the waters run bitter with disrespect, and the fish become too poisoned and unfit to eat. It seems to me, sadly, that we’ve reached that time now.

So what’s next, you might wonder. What’s next is a period of great hope has been prophesized. Some ancestors call it the great healing. Many believe we are entering the times of the great healing now. But the great healing is not a spectator sport. It’s a critical call to action. All peoples, of all races and religions, must come together and work for the good of all. And in order for any change or healing to take place the truth must be told, and received on compassionate ears.

“The truth must be told, and received on compassionate ears.” The effort to understand old myths and uncover truth is an important part of the process of decolonization. I want to talk briefly about the myths of Thanksgiving, and I hope our ears can be full of compassion.

There is an idea that the Europeans conquered the Native nations by their superior weaponry and military might. This holds a partial truth. The Europeans did try to conquer and control every indigenous nation they encountered. But it would not have been possible without another factor. Between 1492 and 1650, possibly 90% of the Indigenous people of the Americas were killed by plague and other European diseases, to which they had no immunity. The Europeans, unwittingly and often purposefully, brought an unprecedented apocalypse to this land.

Millions upon millions of people died. And this figures importantly in the New England story.

In 1617, a few years before English settlers landed, an epidemic began to spread through the area that became southern New England. It likely came from British fishermen, who had been fishing the waters off the coast for decades, and also capturing Native people for slavery. By 1620, 90 to 96% of the population had died. Villages were left with so many bodies, that the survivors fled to the next town, and the disease continued to spread. It was a catastrophe never before seen anywhere in the world.

It is hard even to imagine it. It devastated the tribes, and left many of their villages empty. One of those villages was Patuxet. When the English settlers arrived in Plymouth harbor they found a cleared village, with fields recently planted in corn. This was a big part of the reason they chose it for their settlement. All of the village’s people had died from the epidemic, except for Tisquantum, whom we know as Squanto. We never usualy hear the whole story about Squanto either. We hear that he taught the settlers how to plant corn and fish and hunt the local area. When I first heard that, I remember wondering how it was he spoke English.

Well, here is the story told by James W. Loewen.*

As a boy, along with four Penobscots, he was probably stolen by a British captain in about 1605 and taken to England. There he probably spent nine years, two in the employ of a Plymouth merchant who later helped to finance the Mayflower. At length, the merchant helped him arrange a passage back to Massachusetts.

He was to enjoy home life for less than a year, however. In 1614, a British slave trader seized him and two dozen fellow Indians and sold them into slavery in Malaga, Spain. Squanto escaped from slavery, made his way back to England, and in 1619 talked a ship captain into taking him along [as a guide] on his next trip to Cape Cod.

… now Squanto walked to his home village, only to make the horrifying discovery that he was the sole member of his village still alive. All the others had perished in the epidemic two years before.

Perhaps this was why he was willing to help the Plymouth Colony which had settled in his people’s village. Another theory holds that he was sent there by the Wampanoag chief or Sachem, Massasoit, to keep an eye on them. It was a depleted and downhearted people who had survived the epidemics. Perhaps they thought it might prove beneficial to make an alliance with these newcomers.

The settlers, too, had lost half their people during the first hard winter. There were only 53 settlers who survived until the harvest festival that was later declared to be the first Thanksgiving. One theory suggests that when the settlers sent out men to hunt for fowl for the feast, the Wampanoags heard the gunfire and went to investigate. Massasoit and 90 of his men arrived. Seeing a harvest festival going on, they went out hunting and brought back 5 deer as a gift, and they all ate together and visited for three days. It was a brief moment of tentative peace. Colonization continued, and one generation later, the English settlers and the Wampanoag were at war.

For many Native people in our time, the day called Thanksgiving has become a Day of Mourning, to remember the hundreds of years of losses suffered by their peoples. But the story that is held up, the story that is remembered in elementary schools with fun pageants about Pilgrims and Indians, is a story that indicates all was well. This myth of Thanksgiving helps to erase the troubling history of genocide in our country.

Now, I know that what we share with children is often simplified and made more gentle. But I couldn’t help but contrast this approach to what I have read about how German people acknowledge the history of the Holocaust in their country.

Every German school child must visit a concentration camp; as essential a part of the curriculum as learning to write or count. The country’s cities are landscapes of remembrance. Streets and squares are named after resisters. Little brass squares in the pavements …contain the names and details of Holocaust victims who once lived at those addresses. Memorials dot the streets: plaques commemorating specific persecuted groups, boards listing the names of concentration camps…, a giant field of grey pillars in central Berlin attesting to the Holocaust.

What might it look like if we in our country acknowledged the devastating underpinnings of our own history? If we acknowledged the land thefts, the diseases, and the forced march relocations; the boarding schools that Indian children were forced to attend whose purpose was to wipe out Indigenous languages and cultures? What if we acknowledged the church’s role in this history?

But this country does not want to acknowledge its past, because in fact, it has not ended the colonization process—our understanding of our history is directly linked to our current social landscape. One of the effects of the myths about Columbus and Thanksgiving is to situate stories of Indigenous people in the distant past. To make disappear the ongoing pervasiveness of the colonization process.

Even when European Americans begin to acknowledge the real stories, and become aware of the devastation suffered by Indigenous peoples, we might feel a sense of disconnection—after all, we think, it wasn’t me, personally, who stole Indian land, or caused disease among the people, or took away children or killed anyone. Perhaps some of us might feel a sense of guilt by association, for what our ancestors have done. But we still imagine it as something long ago and far away.

However, land taking and destruction continue into the present day. For example, just this past week, November 15, 2017, the Old Town Planning Board gave final approval for a mega-expansion of the Juniper Ridge Landfill. This landfill expansion directly threatens the Penobscot River, which is the water home of the Penobscot people. The site is used for out-of-state waste storage. The US Army Corp of Engineers has also approved the expansion, and made the determination not to hold a public hearing on the project.

Back in June of this year, the 1st U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in Boston sided by a 2-to-1 majority with a 2015 ruling by U.S. District Judge George Singal that the Penobscot Indian Reservation includes the islands,“Indian Island… and all islands in that river northward,” but not the river itself. The 1st Circuit dismissed a claim that the Penobscot Indian Nation’s sustenance fishing rights were threatened.

In a dissenting opinion, Circuit Judge Juan Torruella noted that treaties signed in 1796, 1818 and 1833 preserving the Penobscot’s sustenance fishing rights “only make sense and can only be exercised” if their reservation includes at least part of the water of the river. Ironically, even the federal government sided with the Penobscots in this case, arguing that at least the river to the mid-line should belong to the reservation. This was a taking of Indian land done by our own state government in collusion with Federal judges.

In a dissenting opinion, Circuit Judge Juan Torruella noted that treaties signed in 1796, 1818 and 1833 preserving the Penobscot’s sustenance fishing rights “only make sense and can only be exercised” if their reservation includes at least part of the water of the river. Ironically, even the federal government sided with the Penobscots in this case, arguing that at least the river to the mid-line should belong to the reservation. This was a taking of Indian land done by our own state government in collusion with Federal judges.

Colonization in the form of land-taking and destruction continues into the present day. These are just two of many more examples I could name. From oil pipelines at Standing Rock, tar sands oil in Canada, uranium mining in Nevada, to sports team mascots and name-calling. Understanding our history can help us to understand the present.

I want to ask you to look again at the four slips on which you wrote things that are precious to you. That which you are most thankful for. Identify at least one slip that represents the kind of things that might have been taken from Native people, such as home, land, family, children, language, spirituality. I ask you to surrender this slip to my helpers as they go around with baskets. I will be reading what you give to them. …

Now look at what remains in your hand, the three slips you have left. In the spirit of feeling what has happened in colonization, we are going to come around again and take another slip from each person and read them aloud. This time the helpers will take whatever slip they want.

I invite all of us to pause for a moment, and notice our feelings and responses to the loss of these precious items.

And what if I were to offer a prayer of thanks that these items were now mine?

Of course, this simulation was symbolic, not actual, and the takings from Native people occurred relentlessly over generations, in so many aspects of their lives. So we really can’t appreciate the magnitude of what has happened in our country.

One first step in the pursuit of decolonization is to listen to Indigenous people’s stories of loss and pain. Listening is not about fixing something, or feeling guilty, or giving advice. Listening is about being present and opening our hearts to the experience of someone who has a story to tell. We need to let our hearts be broken by the stories. Healing begins to be possible through telling the stories and through listening to the stories with compassion. When we listen together, there is hope.

I mentioned earlier that so many of us are now carrying trauma in our hearts from what is happening to our country and to the earth in these times. I believe that we can’t solve the problems of today, without being open to the roots of our society’s destructiveness. All of us need this truth-telling. All of us need a time of healing. I find hope in the Indigenous prophecy that we are entering a time of healing.

Maria Girouard finished her talk about the Seven Fires Prophesies with these words:

Interestingly enough, our traditional teachings tell us that this new change, this new move towards a new harmonious world, will begin in the East. And it is supposed to sweep across Turtle Island like the dawn of a new day. So here we are, perfectly positioned in Wabanaki land where the light from a new day first touches Turtle Island. … Thank you very much, you are pleasing to the eye, I’m glad you are here. The ancestors have been expecting us.

*From James W. Loewen, “Plagues & Pilgrims: The Truth About the First Thanksgiving,” in Rethinking Columbus, p. 81.

Opening Words

Opening Words  Winona LaDuke is the executive director of Honor the Earth, and an Ojibwe activist and economist on Minnesota’s White Earth Reservation. She writes:

Winona LaDuke is the executive director of Honor the Earth, and an Ojibwe activist and economist on Minnesota’s White Earth Reservation. She writes: In a dissenting opinion, Circuit Judge Juan Torruella noted that treaties signed in 1796, 1818 and 1833 preserving the Penobscot’s sustenance fishing rights “only make sense and can only be exercised” if their reservation includes at least part of the water of the river. Ironically, even the federal government sided with the Penobscots in this case, arguing that at least the river to the mid-line should belong to the reservation. This was a taking of Indian land done by our own state government in collusion with Federal judges.

In a dissenting opinion, Circuit Judge Juan Torruella noted that treaties signed in 1796, 1818 and 1833 preserving the Penobscot’s sustenance fishing rights “only make sense and can only be exercised” if their reservation includes at least part of the water of the river. Ironically, even the federal government sided with the Penobscots in this case, arguing that at least the river to the mid-line should belong to the reservation. This was a taking of Indian land done by our own state government in collusion with Federal judges.

Thanksgiving is a holiday that always fills me with mixed feelings. Gratitude is wonderful, and getting together with family and friends can be a blessing. But I know that the stories we celebrate are white-washed versions of a history that has brought devastation to so many. I always remember that many Indigenous people call this the Day of Mourning.

Thanksgiving is a holiday that always fills me with mixed feelings. Gratitude is wonderful, and getting together with family and friends can be a blessing. But I know that the stories we celebrate are white-washed versions of a history that has brought devastation to so many. I always remember that many Indigenous people call this the Day of Mourning.