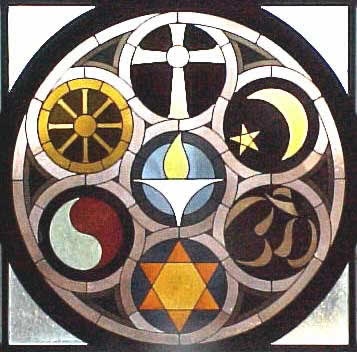

I have found spiritual companions in Unitarian Universalism. Its congregations now include people of many different spiritual beliefs: Christians, Jews, Buddhists, Muslims, atheists, pagans. We include people who believe in a personal kind of God, and those who believe in a divine force of connectedness between everything that exists. We include people who love the Goddess, and people who do not imagine any God at all. Sometimes people say that in Unitarian Universalism you can believe whatever you want—but that is not really true. Though we have many more diverse beliefs today as Unitarian Universalists, you could say we are still arguing with Calvin.

I have found spiritual companions in Unitarian Universalism. Its congregations now include people of many different spiritual beliefs: Christians, Jews, Buddhists, Muslims, atheists, pagans. We include people who believe in a personal kind of God, and those who believe in a divine force of connectedness between everything that exists. We include people who love the Goddess, and people who do not imagine any God at all. Sometimes people say that in Unitarian Universalism you can believe whatever you want—but that is not really true. Though we have many more diverse beliefs today as Unitarian Universalists, you could say we are still arguing with Calvin.

We don’t believe in a God of anger. We don’t believe that people are born evil. We don’t believe that our bodies are shameful. We don’t believe that someone had to die to appease an angry God. We don’t believe that God loves some people and sends other people to hell. We want to get rid of that guilt and shame producing kind of religion, that heavy burden people still carry around because Calvinism is so ingrained in our culture.

We do believe that Love is at the center of the Universe, and those of us who believe in a God, believe in a God of Love. We do believe that each person is important and lovable and that we are all part of one family. We do believe that we are called to live a life of service and compassion, and that human beings, however imperfect we may be, can make a choice to follow our values.

We believe in a democracy of spirit—that each person has a share of wisdom and truth and love. We believe in the importance of community—that we learn and grow most by sharing with each other. We believe that love is contagious, that we cannot find fulfillment and purpose without knowing that we are loved, and loving others. We believe that love can transform lives.

To believe in Love as the foundation of the universe is an act of faith. There is no proof, we don’t know in some objective way that love will win out over the forces of hate and greed. We have to make an experiment of it—perhaps that is why the Quakers could sing “Love is Lord of Heaven and Earth” with such conviction. They practiced nonviolent love in their doings with other people, and learned something of its strength. And perhaps we too have experienced something of its power in our times—those moments when gentleness transformed a heated situation, those historic movements when love crumbled oppression and brought justice into society.

To believe in Love, to make this act of faith, is to strengthen Love’s power in our world, to make it more likely that our relationships will be mutual and kind, that our society will bend toward fairness and compassion. May it be so.