I have a feeling of glee because I am taking a class at the University of Southern Maine. Well, actually I am auditing it. I discovered that anyone 65 and over can audit classes almost for free (compared to actual tuition costs). I had to pay a $55 “transportation” fee, and then learned that with my student ID (I have a student ID!) I can take the metro bus for free. So many new things, and it reminds me of my excited feelings of going back to school when I was a kid.

I have a feeling of glee because I am taking a class at the University of Southern Maine. Well, actually I am auditing it. I discovered that anyone 65 and over can audit classes almost for free (compared to actual tuition costs). I had to pay a $55 “transportation” fee, and then learned that with my student ID (I have a student ID!) I can take the metro bus for free. So many new things, and it reminds me of my excited feelings of going back to school when I was a kid.

But I am especially excited about this class, Wabanaki Languages, taught by Roger Paul, whom I got to know through the Decolonizing Faith project in which I am involved. Roger is really fun and funny and is a native speaker of the language, and a fountain of history and understanding. We’ll be learning “oral history of Wabanaki languages and stories of Wabanaki elders passed from generation to generation,” along with vocabulary and pronunciation and the like.

For those who are not from this area, the Wabanaki peoples are the Indigenous people of Maine, and there are four distinct modern tribal communities, but as Roger tells us, they are not really so distinct. It was Europeans who thought of them as different from each other. The people lived in villages where the food supply would support them (mostly hunting, fishing and gathering) and when the group grew too large for that system, they would start a new village down river or at the next river. So the languages are variations of the same tongue, and the people were identified by the places they lived, or by characteristics of those places.

Most of the students in the class are Wabanaki tribal members learning to speak their own language, as much was lost during the era of boarding schools. Now there are efforts among children and adults to revitalize the language while there are still Native speakers. Roger has been involved in teaching children on the reservation. But why am I interested, as a white person, to learn this language? Years ago, when I was first learning about the challenges that face Indigenous people, I got involved in the issue of cultural appropriation–the theft of Native spiritual practices by non-Native peoples, especially in New Age settings. (See more on that at Wanting to Be Indian.)

I remember one Indigenous writer saying, “If you really want to learn about our spirituality, learn our language.” I’ve learned a lot from Native authors such as Robin Wall Kimmerer talking about some of the key differences between Indigenous language and English. Particularly, Kimmerer speaks about the idea of animacy and inanimacy as embedded in the syntax. Trees, animals, plants, rivers are never referred to as “objects” or as “it” in her language. They are alive, animate. All the verbs and pronouns are organized around whether you are referring to something alive, or inanimate. The language we speak affects how we think about our world. The English language has colonized this place, made the land and water and creatures into “its.”

I want to learn Wabanaki Languages to better understand Wabanaki people and culture, and this place in which I live, the language native to this place. I want to help decolonize my mind, and learn to think in a new way.

So right after my

So right after my  After doing the first batch, which used a lot of water, I figured out that I should save the wash water and bring it out to the garden, where I put it on the kale plants! Then I spinned the kale pieces to dry them, and sautéed them in our big cast iron pan. I had to start with about half of the batch, then add the second half after the first had cooked down a bit. I had green curly kale, red or purple curly kale and a double batch of lacinato kale. After sautéing, I cooled them in a bowl in the refrigerator before putting in bags. On the recommendation of other online gardeners, I used a straw to pull out all the air in the bags.

After doing the first batch, which used a lot of water, I figured out that I should save the wash water and bring it out to the garden, where I put it on the kale plants! Then I spinned the kale pieces to dry them, and sautéed them in our big cast iron pan. I had to start with about half of the batch, then add the second half after the first had cooked down a bit. I had green curly kale, red or purple curly kale and a double batch of lacinato kale. After sautéing, I cooled them in a bowl in the refrigerator before putting in bags. On the recommendation of other online gardeners, I used a straw to pull out all the air in the bags.

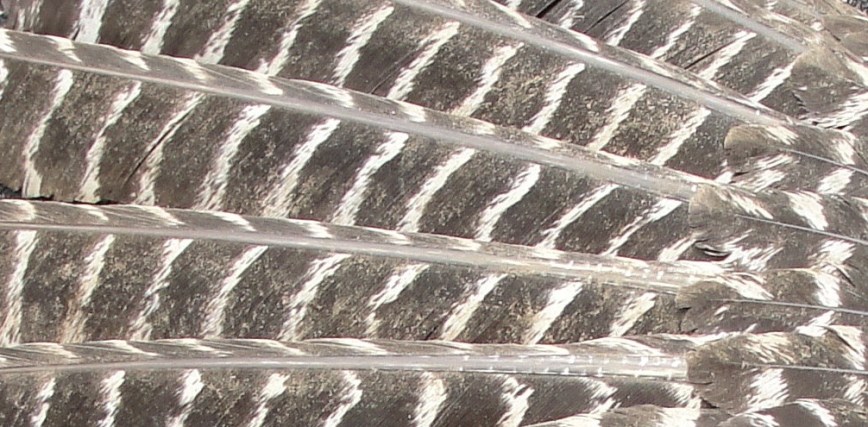

I think of the wing of a bird

I think of the wing of a bird

Today I finished the harvest of St. John’s Wort–all from plants that grew up wild in our yard, or down the street from our home. I had cut the flowers with a little bit of plant attached, back when they were in full bloom, in early July. I dried some of it in tied bunches hanging in the garage, and some of it in loose bunches on an extra window screen laid flat in the basement. (Take note: I definitely preferred the screen method for later processing ease.)

Today I finished the harvest of St. John’s Wort–all from plants that grew up wild in our yard, or down the street from our home. I had cut the flowers with a little bit of plant attached, back when they were in full bloom, in early July. I dried some of it in tied bunches hanging in the garage, and some of it in loose bunches on an extra window screen laid flat in the basement. (Take note: I definitely preferred the screen method for later processing ease.)

I blogged about

I blogged about  But last week, with more compost and soil, I finally brought the beds up to level, and then finished them off with a layer of wood chips. In the bed near the garage, I actually created two little pockets with cut out pots for the ones that were still too small, so I could fill the soil around them up to level. They would have been buried! Hopefully, they’ll get enough sun and water to keep growing and come back next year with a flourish.

But last week, with more compost and soil, I finally brought the beds up to level, and then finished them off with a layer of wood chips. In the bed near the garage, I actually created two little pockets with cut out pots for the ones that were still too small, so I could fill the soil around them up to level. They would have been buried! Hopefully, they’ll get enough sun and water to keep growing and come back next year with a flourish. Transitions create a liminal time, a time on the threshold between old and new, between past and future, a sacred time, perhaps a dangerous time. Yesterday, I turned in my keys to the congregation where I had ministered for 13 years. My retirement is official. But who am I now?

Transitions create a liminal time, a time on the threshold between old and new, between past and future, a sacred time, perhaps a dangerous time. Yesterday, I turned in my keys to the congregation where I had ministered for 13 years. My retirement is official. But who am I now?